poetry lounge: “to be nobody but yourself.” {e.e. cummings}

Welcome to the Poetry Lounge. Here you can escape, for a moment, the banal echoes of ordinary life.

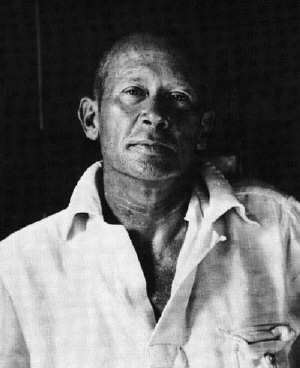

Our special guest today is Edward Estlin Cummings (otherwise known as e.e.), born in Cambridge, Massachusetts on October 14, 1894.

You could say that Edward was called to poetry, beginning his explorations of poetic writing at the age of eight.

“Such was a poet and shall be and is—who’ll solve the depths of horror to defend a sunbeam’s architecture with his life: and carve immortal jungles of despair to hold a mountain’s heartbeat in his hand.” ~ e. e. c.

E. E. Cummings made me notice poetry—really see it for the first time—during a period of my life which consisted mostly of comic books and science fiction novels.

I was a late bloomer to poetry and literature. I was intelligent but not intellectual; philosophical but unsophisticated in my philosophical thinking because I hadn’t yet read up on the philosophers.

As for poetry—it may as well have been a foreign language spoken by an idiot, signifying nothing. It did not sing a song that moved my heart. Music did that for me, but my soul was deaf to poetry… until the day I started hanging out with poets.

Anybody can learn to think, or believe, or know, but not a single human being can be taught to feel… the moment you feel, you’re nobody-but-yourself.

I was twenty-one and I’d just been kicked out the Air Force over a difference of opinion of what I should be doing with my life.

I wanted to learn Russian and be a translator and eventually a diplomat and the Air Force wanted me to stand guard at one of their bases somewhere or reverse-engineer an insect into a biological weapon—at least, that’s what I assumed I would be doing if I became an Entomology Specialist.

I didn’t enlist with a guaranteed job and they screwed me over for it — but that’s another story of poor judgment and idealism gone awry.

“Great men burn bridges before they come to them.” ~ e. e. c.

Back home, feeling raw and quite the failure, I fell in with a group on poets that hung around the campus of the University of Oregon.

Late nights of listening to music and hanging out at Lenny’s Nosh Bar led to my inclusion in a poetry show they were putting together that was called Dancing With Zelda—as a homage to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s stormy relationship with his wife.

The show was a mixture of original poems by my poet friends and poetry by Dylan Thomas, T.S. Eliot and E. E. Cummings, among others.

This is the first poem that grabbed me:

anyone lived in a pretty how town

(with up so floating many bells down)

spring summer autumn winter

he sang his didn’t he danced his did

Women and men (both little and small)

cared for anyone not at all

they sowed their isn’t, they reaped their same

sun moon stars rain

children guessed (but only a few

and down they forgot as up they grew

autumn winter spring summer)

that no one loved him more by more

when by now and tree by leaf

she laughed his joy she cried his grief

bird by snow and stir by still

anyone’s any was all to her

someones married their everyones

laughed their cryings and did their dance

(sleep wake hope and then) they

said their nevers they slept their dream

stars rain sun moon

(and only the snow can begin to explain

how children are apt to forget to remember

with up so floating many bells down)

one day anyone died i guess

(and noone stooped to kiss his face)

busy folk buried them side by side

little by little and was by was

all by all and deep by deep

and more by more they dream their sleep

noone and anyone earth by april

wish by spirit and if by yes.

Women and men (both dong and ding)

summer autumn winter spring

reaped their sowing and went their came

sun moon stars rain

Wow! What was this arrangement of words that was giving me goose flesh and making my insides feel strange?

It was spine-tingling truth, that’s what it was. I had never read anything like it. It knocked my socks off.

One of the coolest things about it to me was that Cummings clearly didn’t give a damn about punctuation or any of the other rules of writing that I was always inexplicably resentful to follow but did so dutifully.

There was something so simple and elegant and unpretentious about the writing that appealed to me.

I was also in that phase of life when falling in love was pretty much the best thing ever. It was the ever present ache. And Cummings spoke the language of that ache in words that were honest and completely stripped of ambiguity.

somewhere i have never traveled, gladly beyond

any experience, your eyes have their silence:

in your most frail gesture are things which enclose me,

or which i cannot touch because they are too near

your slightest look easily will unclose me

though i have closed myself as fingers,

you open always petal by petal myself as Spring opens

(touching skilfully, mysteriously) her first rose

or if your wish be to close me, i and

my life will shut very beautifully, suddenly,

as when the heart of this flower imagines

the snow carefully everywhere descending;

nothing which we are to perceive in this world equals

the power of your intense fragility: whose texture

compels me with the color of its countries,

rendering death and forever with each breathing

(i do not know what it is about you that closes

and opens; only something in me understands

the voice of your eyes is deeper than all roses)

nobody, not even the rain, has such small hands

I think of this poem as the most used arrow in Cupid’s quiver, drenched in the same juice of the flower that Puck used to make a Fairie Queen fall in love with a man with the head of an ass.

It is one of the most unabashedly romantic love tokens I’ve ever read, as compelling as anything ever uttered by Romeo Montague or Cyrano de Bergerac. It has the effect of a magic spell.

And, when it comes to expressing the carnal aspect of love, nobody gets down and dirty like the master poet.

But, e. e. cummings (his lowercase nom de plume) was no mere sonneteer. Reading his poetry is like listening to the blues. His poetic spirit plays mischievous surrealistic games in Paris with the Dadaists.

pity this busy monster, manunkind,

not. Progress is a comfortable disease:

your victim (death and life safely beyond)

plays with the bigness of his littleness

—electrons deify one razorblade

into a mountainrange; lenses extend

unwish through curving wherewhen till unwish

returns on its unself.

A world of made

is not a world of born—pity poor flesh

and trees, poor stars and stones, but never this

fine specimen of hypermagical

ultraomnipotence. We doctors know

a hopeless case if—listen: there’s a hell

of a good universe next door; let’s go

Is this the poetry of quantum physics and parallel worlds? I dunno. But, this poem has always defied my attempts to explain it because it’s layered with meaning. Like the way photons affect subatomic particles, the act of observing the poem changes it.

In 1917, during the first world war in Europe, Cummings enlisted in the Norton-Harjes Ambulance Corps and was arrested five months later by the French military on suspicion of espionage because he openly expressed anti-war views.

He wrote a novel, The Enormous Room, based on his experiences in the military detention camp in Normandy where he was held for three and a half months. I think of this when I read one of my favorite expressions of misanthropic sarcasm:

Humanity i love you

because you would rather black the boots of

success than inquire whose soul dangles from his

watch-chain which would be embarassing for both

parties and because you

unflinchingly applaud all

songs containing the words country home and

mother when sung at the old howard

Humanity i love you because

when you’re hard up you pawn your

intelligence to buy a drink and when

you’re flush your pride keeps

you from the pawn shop and

because you are continually commiting

nuisances but more

especially in your own house

Humanity i love you because you

are perpetually putting the secret of

life in your pants and forgetting

it’s there and sitting down

on it

and because you are

always making poems in the lap

of death Humanity

i hate you

Something happened to E. E. Cummings toward the end of his life that contradicted the image of him as a bohemian surrealist writer.

Before he died in 1962, he became a Republican and supporter of Senator Joseph McCarthy. I think that, at the end, he must have forgotten the vitality of his earlier poetry and was only making poems in the lap of death.

But, in the Poetry Lounge, I feel that the poems matter more than the poets. And so, I will leave you with this:

let it go — the

smashed word broken

open vow or

the oath cracked length

wise — let it go it

was sworn to

go

let them go — the

truthful liars and

the false fair friends

and the boths and

neithers — you must let them go they

were born

to go

let all go — the

big small middling

tall bigger really

the biggest and all

things — let all go

dear

so comes love

~ E.E. Cummings

*****

{Join us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram & Pinterest}