My Life Had Stood, a Loaded Gun: Emily Dickinson.

“I am nobody! Who are you?

Are you nobody, too?

Then there’s a pair of us — don’t tell!

They’d banish us, you know.

How dreary to be somebody

How public, like a frog

To tell your name the livelong day

To an admiring bog.”

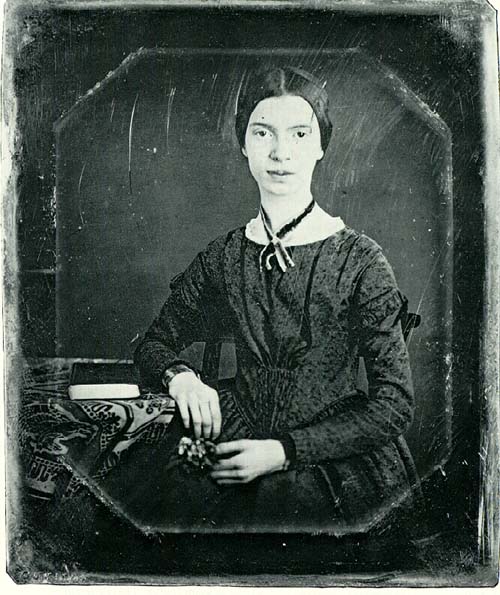

One of the brightest and most lyrically rich introverts of the nineteenth century, Emily Dickinson’s ghost, is still around to haunt us with her slant rhyme poetry, her closed-door mystery and her immortal loneliness.

She wrote nearly 1800 poems throughout her life, publishing less than a dozen, which were highly altered by the publishers to fit the style of the times. The poetry world finally caught up with her literary prowess in 1955 when scholar Thomas H. Johnson published The Poems of Emily Dickinson, the first unaltered version.

Her earliest, heavily edited poetry collection didn’t see the light until 1890, four years after her death. She had made her sister Lavinia promise that she would burn her manuscripts, but thank the verse gods for Lavinia’s better judgment.

Tell all the Truth but tell it slant —

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind —

(1868)

Aside from her verse mastery, Emily’s eccentric personality and lifetime isolation are equally fascinating. After concluding her studies, she spent most of her adult life in her family’s mansion, The Evergreens (Amherst, Massachusetts), now the Emily Dickinson Museum.

Her preference for white clothing and her reluctance to greet visitors, leading to her final confinement in the solace of her room during her last years, add an extra dose of mystery to her story.

Most of her friendship was carried out by correspondence.

The Soul selects her own Society —

Then — shuts the Door —

To her divine Majority —

Present no more —

Unmoved — she notes the Chariots — pausing —

At her low Gate —

Unmoved — an Emperor be kneeling

Upon her Mat —

I’ve known her — from an ample nation —

Choose One —

Then — close the Valves of her attention —

Like Stone —

(1862)

Maybe her raw poetic sensitivity was deeply altered since childhood, with the experience of death after death from loved and admired ones.

Her preoccupation (and, in some cases, visible trauma) with death and immortality, intensified when she was still a teenager, with the death of her cousin, and it grew as she grew, with the passing of each friend, her parents and extended family, who were, in her own words, “called back.”

She followed them at age 55, from Bright’s disease (more modernly known as kidney failure) which is suspiciously related to a lack of Vitamin D.

We know now that the most reliable source of vitamin D is sunlight (with extra help from supplements), but I doubt she’d get access to these futuristic pills, from the depth of her heartbroken nineteenth century, bedroom seclusion.

I felt a Funeral, in my Brain,

And Mourners to and fro

Kept treading — treading — till it seemed

That Sense was breaking through —

And when they all were seated,

A Service, like a Drum —

Kept beating — beating — till I thought

My Mind was going numb —

And then I heard them lift a Box

And creak across my Soul

With those same Boots of Lead, again,

Then Space — began to toll,

As all the Heavens were a Bell,

And Being, but a War,

And I, and Silence, some strange Race

Wrecked, solitary, here —

And then a Plank in Reason, broke,

And I dropped down, and down —

And hit a World, at every plunge,

And Finished knowing — then —

(1861)

I don’t know what it is about Emily Dickinson that I relish the most. Aside from my own Jane Austenish censored spirit and secret infatuation with the literary long dresses of the nineteenth century, maybe it’s the bird-fed nostalgia reflected in her rhymes—that of a simpler, more quiet life I seem to have lived at some point in history (otherwise why would I miss it so badly).

“My business is circumference,” she said in a letter. She was projecting her imagination onto all relationships of man, nature and spirit.

Well, so is mine. And yours. We just use blogs instead of letters.

Five years ago, hiding in a town and house similar to Amherst’s Evergreens, I picked up her first unabridged and unaltered, 1955 Thomas H. Johnson edition and, through an entire autumn of tea and chimney, I thought she and I could have (must have) been awkward friends.

On one hand, she embodies the two ingredients that account for a writer’s freakability levels: the forsaken art of solitude, which she took to new, deadly levels, and her passionate romance with language. Combine this with the mysterious, poetic elegance watching you behind closed doors. Doors you should open but you’d rather not.

But most importantly, perhaps it is the way she laughed in the establishment’s face. The way the publishers of the time tried to cookie-cut her. The way she eventually bled out, but laughed through all her bleeding.

By laugh, I mean, of course cry: she cried through the tips of her fingers, despite the agonizing ignorance from a nonexistent readership (much harder to bear than opposition), day after day, poem after poem, misunderstood, unwanted, but who cares?

Oh, but she did care. Like we all do. She tried to get published. She gave up. Doubted herself. Tried again. Perhaps, according to the long correspondence she maintained with author and abolitionist Thomas Wentworth Higginson, she didn’t try enough?

What matters, in the end, is that she wrote, tirelessly and incessantly, for half a century. That’s the purest, most unaltered meaning of the word “writer” or “poet” or anything you are: You do.

Although, when all is said and done, the lament still remains. You live and hope—some behind closed doors and others with a Bang!—that your gunshot life may echo not just in eternity, but here and now as well, with you still in it.

My life had stood — a Loaded Gun —

In Corners — till a Day

The Owner passed — identified —

And carried Me away —

And now We roam in Sovereign Woods —

And now We hunt the Doe —

And every time I speak for Him —

The Mountains straight reply —

And I do smile, such cordial light

Upon the Valley glow —

It is as a Vesuvian* face

Had let its pleasure through —

And when at Night — Our good Day done —

I guard My Master’s Head —

‘Tis better than the Eider — Duck’s

Deep Pillow — to have shared —

To foe of His — I’m deadly foe —

None stir the second time —

On whom I lay a Yellow Eye —

Or an emphatic Thumb —

Though I than He — may longer live

He longer must — than I —

For I have but the power to kill,

Without — the power to die —

(1863)

————————————————————

[*] A fire capable of erupting like Mount Vesuvius.

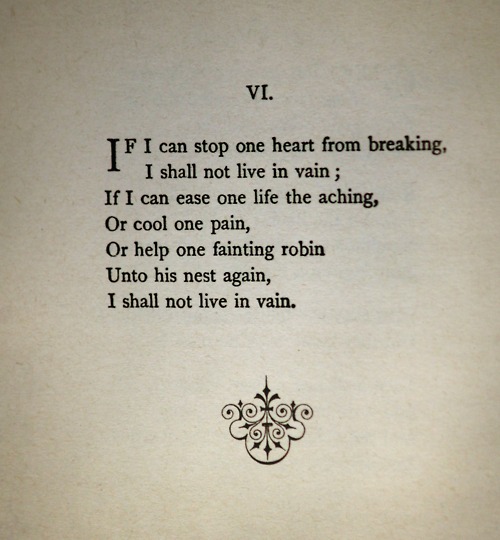

The purpose of art according to Emily Dickinson? Same as that of life:

And the ultimate meaning of poetry, synonymous with all: your art, your life, your You.

“If I read a book [and] it makes my whole body so cold no fire ever can warm me I know that is poetry. If I feel physically as if the top of my head were taken off, I know that is poetry. These are the only way I know it. Is there any other way?”

***

{Join us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram & Pinterest}