Let’s Help Her & Be A Part Of A Story We Never Want To End.

{source}

Humans respond well to patterns. And stories that stick follow certain patterns. Story, as it turns out, is how we internalize and process just about everything — from the baffling to the banal.

Mythologist Joseph Campbell termed this common narrative pattern the Hero’s Journey.

In its simplest form, it has three parts: the hero finds herself in a broken world, then reluctantly answers a call by setting out to overcome huge obstacles. Lastly, she returns with a gift that makes that same broken world more bearable, and is then shared with her community. At our core, we hunger to embark on the hero’s journey.

We want to embody the same compelling narratives we consume. We yearn to get in the story.

Everyday at 7 a.m., a group of girls gather by a river in Kenya to sell their bodies for tuition money. With money in hand, they walk to school, wondering if their education will lead to their liberation.

An organization by the name of LitWorld proposed an alternative ending to this story.

Now, everyday at 7 a.m., that same group of girls gathers in a small room to read, write, listen and share their stories in LitClub, one of many LitWorld-planted, peer-led, centers around the world. LitWorld gifted the girls chickens, and the money from their egg sales displaces the need to prostitute.

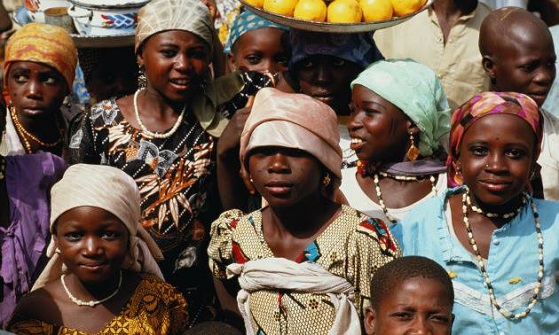

So, what does literacy have to do with these girls, or the kidnapped girls in Nigeria, now missing for over a year? Why is literacy an urgent human right?

It’s easy to blame others for our broken world — the low-hanging fruit of anger and disillusion dangles at eye-level. It’s also easy to let our discomfort shut the door for us. Today, stories swim across wide channels, some are paid for, some are earned — all are shared.

These seemingly divergent narratives form the collective here-and-now of our experience. And just as we yearn to find patterns and make meaning, we also ache to feel useful. If the truth of anything lies in its efficacy, what works and doesn’t work about our response to the missing girls in Nigeria, to the suffering of the disinherited?

Willingly or not, we often retreat into the house of What-We-Can-Handle. And thus we swirl around in an ever-shifting landscape of our own mini-crises.

Yet, the knowledge of these missing girls is lodged in each of us, embedded in the interstitial tissue that connects us to one another.

If we don’t transform our pain, we run the risk of transmitting it. Maybe we need a Law of Conservation of Pain, stating that pain, left alone, cannot be destroyed, yet may be rearranged in space.

How can a banker in Manhattan dry the tears of a brother in Nigeria who scours the forest night and day in search of his sister? How can a mother of three in Ohio possibly help one girl, let alone hundreds, at the hands of an armed captor, somewhere in Africa? In this broken world, will we answer the call of the Hero’s Journey? And how?

Going beyond the storybook version of victim and villain, can we lift the veil of misunderstanding and delusion? Can we acknowledge our oneness, risk our certainty, and re-evaluate the dichotomous concept of evil?

Boko Haram is a terrorist group. It is also a conglomerate of stories, like that of any group. Their perception, that Western education is a sin, is their reality. They too, live in a broken world, and so they lash out in an effort to mend it. No boy dreams of growing up to kidnap and sell innocent girls. Yet, men are created who inhabit their days this way.

If illiteracy is the state of not having knowledge about a particular subject, I would argue that illiteracy is the seed that bears this type of invasive species, whose roots are strangling us all. The tenets of literacy are speaking, reading, writing and listening. There is a critical shortage of listening, to our neighbors, to the ones we hold closest, to ourselves.

In an effort to salve our own wounded hearts, the source of our dis-ease with what is, we often fail to listen. We don’t want to stand in confusion, so we buck against complexity. Yet, as Carl Jung said, “What we resist, persists.” Evidenced by a lack of efficacy, we are not finding our truth among the harsh dividing lines we have drawn.

We must swim down deeper.

Stories are conduits for insights and morals, they weave entire cultures together. They are the underpinning of literacy.

In another pilot project in Nairobi, LitWorld gave 200 mobile phones to girls in the slums so they could have access to a safety network — friends and mentors to listen to their challenges and support their educational, economic and emotional goals. Access, it seems, is the new currency. We can take the old model of school, and improve it.

We can create exponential impact with a slight change of perspective. We can return to the broken world with a gift. If education, as we know it, is a life-threatening endeavor, then maybe education doesn’t have to happen in the confines of four walls; in fact, maybe it shouldn’t.

We can’t eradicate evil but we can displace it with love and non-violent solutions.

We stand at the riverbank, our toes touching the water, our reflections looking up at us. We can swim upstream towards wholeness or float passively towards destruction. In fact, our humanity hinges on this very decision. Our reluctance or eagerness to answer the call of the Hero’s Journey becomes our story. And each of us wants to live a story worth repeating.

The river of wholeness, that leads us back to the bearable broken world, swells with tough conversations, vulnerability, and sacrifice. There are no easy answers. The horror of the mass kidnapping in Nigeria may cause us to wonder if life has meaning, if the world is getting better or worse.

Campbell said, “Life has no meaning. Each of us has meaning and we bring it to life. It is a waste to be asking the question when you are the answer.” But how, you ask? Start with curiosity and vulnerability. Start with letting yourself feel.

The final stage of each of our stories is, according to Campbell, where we come back into the broken world we left, but this time with a gift to share. Now, it’s not about us, but the way each of us can support the community and world at large, in our own unique way.

Here is where the channels of our seemingly disparate narratives converge, where the story of a wailing mother in Nigeria becomes the story of a crushed father in Newtown, where our grief and our joy ebb and flow, carried by the unavoidable waterways of our shared humanity. This, and so many other tragedies, brings me to a raw, disillusioned place.

I want to facilitate a re-action that evolves us. I understand and share the urge to hide and the ease in which our minds create another world, oceans away from our own, where this suffering festers. The world needs our mustard seed of hope, our yearning, often-stumbling steps towards a solution.

It hurts to feel. Yet, the full spectrum of human emotions is a path that we were designed and destined to walk.

Somewhere, right now, in Nigeria, a little girl craves the wonder and magic of learning. Afraid for her life, her parents keep her home, safe from the broken world outside. And day, by day, page by page, the story unfolds. Perhaps access to technology is the gift that we help her bring back to her broken world.

Let us be part of a story that we never want to end. As Arundhati Roy says, “Another world is not only possible, she is on her way. On a quiet day, I can hear her breathing.”

*****

Mary Cinadr is committed to sharing the joy, vitality and self-compassion that writing and Yoga bring her. Mary enjoys leading people to the page as well as the mat. As a memoir and travel-writing coach, and brand consultant, she is interested in how Yoga and writing inform and affect each other and help us author brave lives of authenticity and service. Service, storytelling and creativity are at the heart of Mary’s work and play. She served three years as a Peace Corps volunteer in Paraguay, the first two were spent in a beekeeping suit. She resides in Brooklyn, and enjoys frequent visits to small towns, mountaintops, and campfires.