Let Your Heart Be Broken.

{source}

My friend Cecil died on Wednesday.

I last saw him three weeks ago, when my boyfriend Alan and I delivered a recliner to his little apartment. He’d mentioned to me that his favorite TV-watching chair had broken, and he’d made do with a hard, straight-backed chair since.

When a 78-year-old man with COPD wants a comfortable chair, he should sure as hell have one.

Alan had an old vinyl recliner he was ready to be rid of. We hauled it to Cecil’s and set it up in his living room between the oxygen tanks and a secondhand end table covered in photographs of his family.

We were embarrassed by the well-worn chair. Kitty scratchmarks marred the surface, little tufts of stuffing poking out like fur. Cecil found it perfect. He settled back and sighed happily, saying, “I never expected anything this nice.”

I meant to get back over to his house to check in on him, see how the chair was working out. He lived just a block off my typical walking route. Daisy, my dog, adored Cecil and the bag of dog bones he kept in his pocket at all times.

When we passed his apartment, she dragged me to the front porch, to the laughter that creased his grizzled cheeks. He fed her treats, one after the other, while I kept her feet from tangling his oxygen tube. Then we’d sit and talk for a while about his daughters, the fine weather, fresh summer peaches.

He seemed to breathe easier as he remembered. I mostly listened.

But I didn’t make time to stop by these past three weeks. Just yesterday, hours before I learned he was gone, I made a promise to Daisy, “We’ll go this weekend, I promise.”

It’s cliché to talk about the guilt one feels after a loved one dies. I do feel guilty. I am sorry, so sorry I didn’t make time to go see Cecil one more time.

To sit on his porch and watch him feed my dog and pet her head. To spend a few minutes in the waning light of a summer evening with a man who reminded me so much of my grandfather who died nearly a decade ago.

But beyond the guilt there is this: I didn’t go see Cecil because I knew he was dying, and I was quietly trying to protect myself from what I feel now — the enormous absence of a good man gone. He’d been in and out of the hospital for months. His time was short. I feared the loss.

I tried to soften it for myself by staying away. I failed miserably.

It’s the same reason why I don’t call my grandmother as often as I should. Or why I pick stupid fights with Alan for no reason. Or why I go into hermit-mode when I feel depressed and avoid the loving compassion of my amazing friends.

It’s why all of us create barriers and boundaries to protect our tender, longing selves. This business of being human will break our fucking hearts. It’s messy and complicated and oh-so-terribly sad at times. We use numbness and addiction and anger and acres and walls to keep ourselves from each other.

And yet. And yet…

The longing we have for each other is so obvious and clear.

We are desperate and dying to be near one another. To make eye contact. To touch and hug. To lie in the darkness with our arms around another and know we are not so alone. To hear stories on a front porch in summertime and to remember how it felt to be a child. We want to be seen and heard.

We want to know our lives matter. That our time here on earth was not spent in vain.

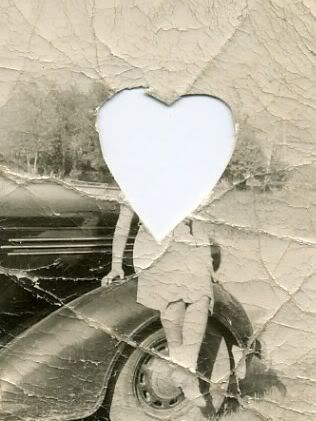

To become fully alive includes the deep and tragic and necessary understanding that we are temporary. In a few more decades, I won’t be remembered. The accomplishments I hold so dear will be long forgotten, diplomas rotting in an attic or a landfill. My face unknown in pictures. My name, a ghost.

But here’s the miracle, the hope, the wildly liberating truth of why we matter: our love lives on. The feeling ripples out from us to others like a stone breaking the still water of a pond. And the reverb is infinite. One small act of love today ripples out to a million others and into the next 1000 years.

Love is our legacy to each other.

My friend Cecil died on Wednesday. He was not a rich man or a famous one. He lived a simple life that ended quietly. But he was endlessly kind to me and to my dog. He smiled and laughed every time I saw him. He told me how much he cared about me.

In spite of my best efforts to avoid it, he helped me break my own heart wide open to this messy and beautiful and tragic and amazing life.

Let your heart be broken.

***

Cynthia Briggs is a professor of counseling, a speaker and consultant, and a writer of fiction and creative non-fiction. She’s the co-editor of Snapdragon: A Journal of Art and Healing. Her memoir and essays have been published in numerous print and on-line journals. She teaches expressive arts and writing in her hometown of Winston-Salem, NC. You could contact her via her website.

***

{Join us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram & Pinterest}