Reducing Stress: What Scientists Learned From Children Who Survived Dutch Hunger Winter.

There was nothing left to eat.

The butter had disappeared in October. By November, adult food rations had been cut to 1000 calories per day. A few months later, in the dead of winter, rations dropped to 500 calories per day. Food stocks throughout the country were empty.

If you were lucky enough to have food ration coupons, you could get 100 grams of cheese every two weeks. Meat was a fantasy. By April of 1945, each person was limited to 1 loaf of bread and 5 potatoes — for the entire week. [1]

It was the middle of terrible famine known as the Dutch Hunger Winter. World War II was nearing an end, and Allied forces were able to push the German army out of the southern half of the Netherlands.

As the Nazis retreated, however, they destroyed docks and bridges, flooded the farmlands, and set up blockades in the northern half of the country to cut off shipments of food and fuel. What little food had been stockpiled and saved was nearly impossible to transport.

Starving and without options, many people ate tulip bulbs and sugar beets.

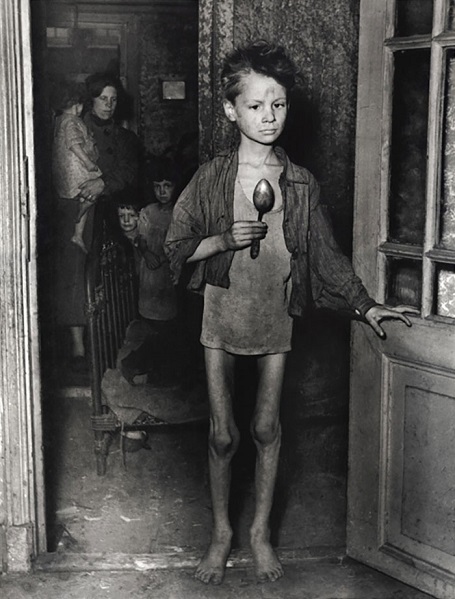

Among those struggling to survive was a 9-year-old boy from Amsterdam named Henkie Holvast. During the worst period of the famine, Henkie was one of the many children who would carry spoons with them wherever they went, just in case.

Photographer Martinus Meijboom captured this iconic image of Henkie during the Dutch Hunger Winter. Two of Henkie’s younger siblings died during the famine. Somehow, he managed to survive.

To make matter worse, winter had come early that year. Canals and waterways had frozen, further restricting food transport. Gas and electricity were either unavailable or inoperable because of the war. The Holvast family, like many others throughout the Netherlands, had begun burning their furniture to stay warm.

By April 1945, the situation was desperate. Approximately 20,000 Dutch had died from malnutrition.

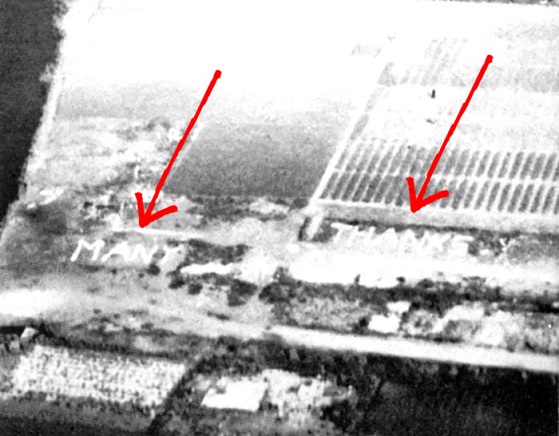

In April 1945, the Royal Air Force flew from Great Britain and coordinated a series of air drops known as Operation Manna. In total, they dropped more than 6,600 tons of food in German-occupied territory. The Dutch responded with a simple message of Many Thanks written in tulips on the countryside.

{source}

The famine mercifully ended the next month, May of 1945, when Allied forces regained control of the Netherlands.

The most surprising part of the famine, however, was just beginning.

The Impact of Stress

As far as famines go, the Dutch Hunger Winter was remarkably unique. Most famines occur in areas that suffer from overpopulation, severe crop failure, or repeated periods of political instability. The Netherlands experienced none of these influences. Once the war ended and Allied troops arrived, the Dutch quickly recovered to a normal diet.

From a scientific perspective, the Dutch survivors were perfect for study. The population consisted of a well-defined group of people who experienced one period of malnutrition at exactly the same time.

In the 1990s, Dr. Tessa Roseboom, a medical faculty member from the University of Amsterdam, began diving into the data about the children conceived and born during the Dutch Hunger Winter. Thanks to meticulous record keeping by the Dutch, Roseboom was able to track thousands of the children throughout their lives.

What she discovered was remarkable. [2]

According to Roseboom’s research, children who were conceived during the Dutch Hunger Winter have:

- Higher risk of cardiovascular disease as an adult (up to 2x greater risk)

- Higher rates of obesity throughout life

- Increased risk of high blood pressure as an adult

- Higher rates of hospitalization as an adult (i.e. increased illness)

- Lower likelihood of being employed [3]

In other words, the children who were still in their mother’s womb during that brutal winter have poorer health six decades later. These studies were groundbreaking because they revealed just how deeply stress can burrow into our lives.

Not only do the effects of stress and malnutrition impact us at the time they occur, they can have lingering effects on ourselves and our children for decades to come.

Stress In Our Lives

The studies on the Dutch Hunger Winter offer a clear and dramatic look at how stress changes our bodies and stays with us throughout our lives. While we don’t have to live in such extreme situations, we do deal with stress on a day-to-day basis.

Because this is something we deal with every day, our best defense against the effects of stress is to build daily habits that counteract those effects.

In other words, reducing stress isn’t something that only those in dire circumstances need to consider. It is something we all need to handle. And the research above makes it clear: reducing stress is something you need to do not only for yourself, but also for your children and grandchildren as well.

Now for the million dollar question: What can we do to reduce stress in our lives?

7 Scientifically Proven Ways to Reduce Stress

Here are 7 scientifically proven ways to reduce stress in your life.

Exercise: I can’t tell you how many times exercise has saved my sanity. If I didn’t lift weights consistently, I wouldn’t have a business. The stress of entrepreneurship would have run me into the ground by now. There are many studies linking exercise to reduced stress levels.

My method of choice is strength training or sprinting, but all types of exercise are useful. (Yoga, for example.)

Meditation/Deep breathing: Yes, meditation can reduce stress. [4-6] That’s probably not a surprise. If you’re like me, then you know meditation is good for you, but you just never find a way to fit it in. Here’s a tip I recently got from a monk: start your meditation habit by meditating for 1 minute. Do that for a month.

Then increase to 2 minutes and do that for a month. And so on, until you get to the level you desire. Talk about slow gains. I love it!

Music: Listening to music can actually trigger the release of stress-reducing chemicals in the body, which is pretty awesome. [7,8]

Sleep: If you are feeling stressed, a nap or a solid 8 or 9 hours of sleep can really help. In some cases, sleep is not only the solution, but actually the problem. Sleep deprivation can be brutal on your health. Most people aren’t getting enough sleep each night, and sleep debt is a cumulative problem.

The stress of too little sleep can add up, and the only real solution is to give yourself the chance to rest. Make time to rest and rejuvenate now, or make time to be sick and injured later.

Laughter: Everything is better when you laugh, including your stress levels. [9-11]

Stand up straight: Surprisingly, research from Harvard has revealed that your body language can impact the amount of testosterone and cortisol in your bloodstream.

[youtube]Ks-_Mh1QhMc[/youtube]

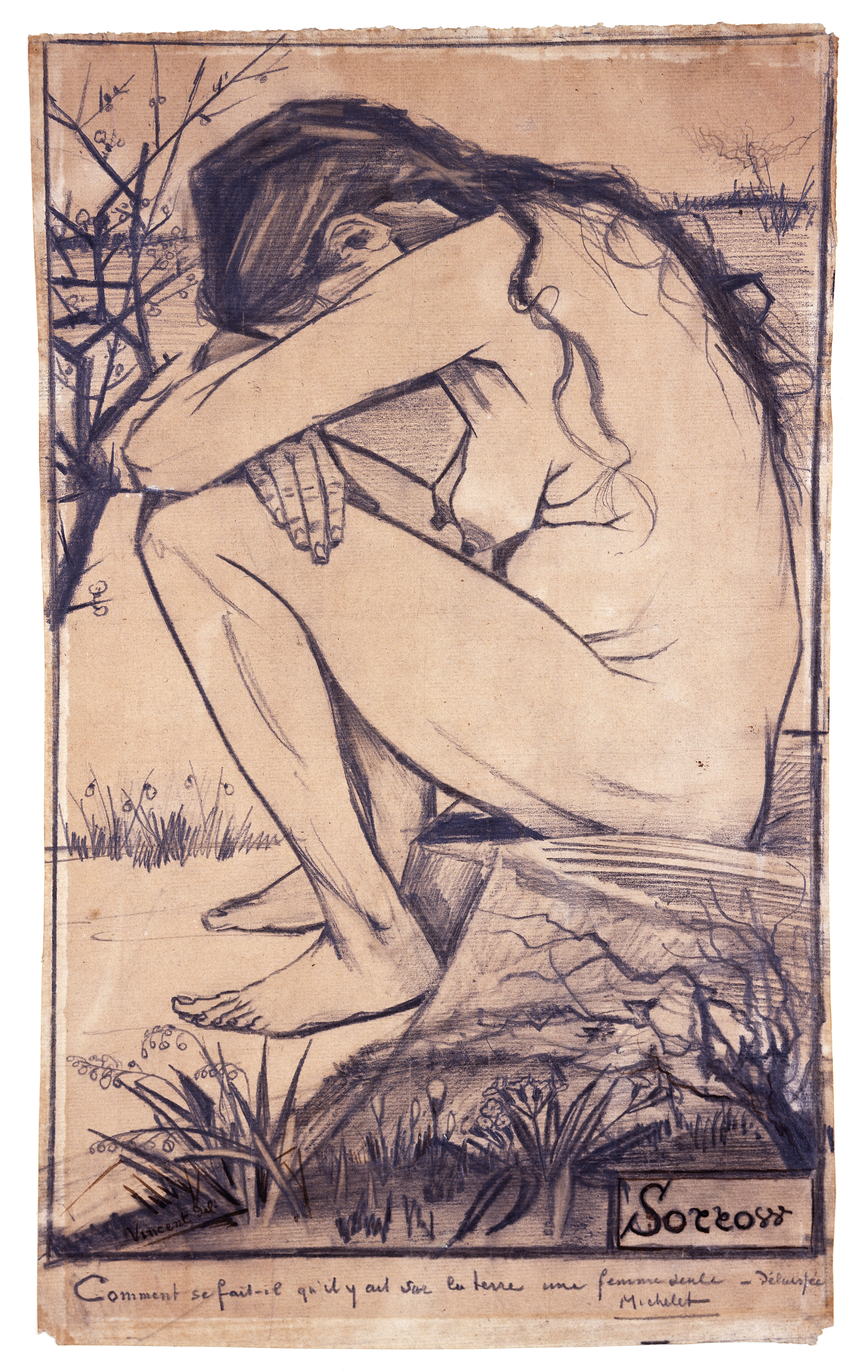

Art: Don’t confuse creating art with being artistic. What we are really talking about here is creating something rather than sitting around and passively consuming. Worrying about all of the things on your to-do list is passive, and naturally provides a feeling of being out of control.

Creating something — whether that means writing in a journal, taking a photo, crafting a ceramic pot, and flashing your scrapbooking skills — naturally makes you feel in control of something and gives you a healthy outlet for your energy.

Where to Go From Here

Thankfully, most of us will never have to live through a period of intense stress like the Dutch Hunger Winter. That said, stress is still part of our daily lives, and it is perhaps the greatest burden to our long-term health. Stress can decrease your heart health. It can increase the rate at which you age. It can disrupt your immune system.

The best path forward is to build stress-reducing habits into our lives (like the ones listed above), so that we can curtail the long-term impact that it has on us and our loved ones.

This article was originally published on JamesClear.com.

Sources

- Technically, rations were measured exactly as 400 grams of bread and 1 kilogram of potatoes. This is approximately 1 loaf of bread and 5 large potatoes.

- Effects of Prenatal Exposure to the Dutch Famine on Adult Disease in Later Life: An Overview by Tessa J. Roseboom, Jan H.P. van der Meulen, Anita C.J. Ravelli, Clive Osmond, David J.P. Barker, Otto P. Bleker

- Long-Run Effects on Gestation During the Dutch Hunger Winter Famine on Labor Market and Hospitalization Outcomes by Robert S. Scholte, Gerard J. van den Berg, and Maarten Lindeboom

- Mindfulness-based stress reduction by Marchand

- A randomized, controlled trial of meditation for work stress, anxiety and depressed mood in full-time workers by Manocha, Black, Sarris, and Stough

- Effects of mental relaxation and slow breathing in essential hypertension by Kaushik, Kaushik, Mahajan, and Rajesh

- From music-beat to heart-beat: a journey in the complex interactions between music, brain and heart by Cervellin and Lippi

- Emotional foundations of music as a non-pharmacological pain management tool in modern medicine by Bernatzky, Presch, Anderson, and Panksepp

- Effects of laughter therapy on postpartum fatigue and stress responses of postpartum women by Shin, Ryu, and Song

- A case of laughter therapy that helped improve advanced gastric cancer by Noji and Takayanagi

- Laughter and depression: hypothesis of pathogenic and therapeutic correlation by Fonzi, Matteucci, and Bersani

***

{Join us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram & Pinterest}