Sung Home: Chapter Forty Three. {fiction}

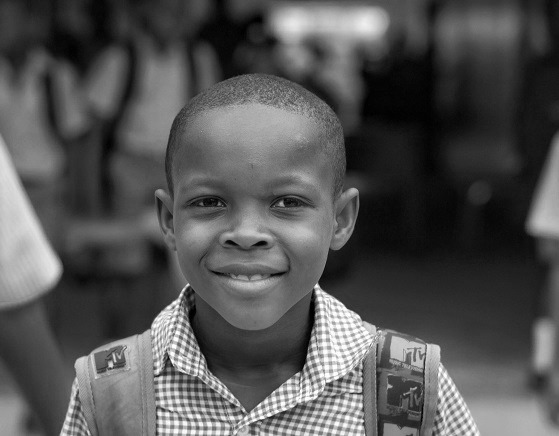

“One day, when I was 10 years old,” he continued, “we arrived at school to find that our teacher had boxes stacked up next to her desk.

A computer company had donated a new kind of computer for us to try. I know now that we were part of some research they were doing, but at the time we were all just excited to be getting laptops. Except, they did not come with instructions at all. Either our teacher didn’t know how to use them either, or she had been instructed not to tell us. There were about 15 of us in the school and we each got one.

The school had electricity, so we had a way to keep them charged although we did not have electricity at home. Our teacher said, ‘You are smart children. I know you can figure out how to work them.’ And she just watched us as we opened our boxes, figured out how to plug in the power cords, opened the lids and started pushing buttons.

Pretty soon we were playing the games that had been installed on the computers, at first ignoring the word processing programs, the calculators and the like. I was hooked!”

“I remember reading about how they did that, just handing kids computers who had never had one, just to see if they had designed the computer intuitively enough for the kids to figure them out. A huge success, as I recall,” said Frank.

“I heard about it too, in Hong Kong,” said Ching Shih. “There was talk at some of the tech companies there of doing something similar in East Asian rural areas too. I remember being amazed that children who didn’t even have electricity in their homes could just figure out computers like that.”

“Yes, we had reporters show up and interview all our families. It was funny, to see all these foreign strangers coming to see us, acting like we had done something extraordinary. But really, we were just children doing what children will do if they are allowed. We were exploring something interesting: playing. Playing is very important to learning, you know.”

“So from then on, you just thought, ‘I’m going into computers when I grow up?’” asked Victorio.

“No, it wasn’t quite that simple,” Tochuku grinned wryly, “we didn’t know it, but our computers were monitored. The first child to successfully learn how to use every program on the computer would be chosen for instruction at a special school in Abuja. I was that child. Not only was I sent to that school, but my family was given a small house to live in on campus while I went there.

My sisters were able to attend the school too, since they didn’t want to separate family members. And they had done well with their computers too.

I began to see possibilities I hadn’t imagined before. There was a student at my school who invented a portable solar water pump for use in springs or wells, and another who invented a portable UV wand to disinfect water. The two spoke all over the country about how to use these together. They improved people’s access to potable water dramatically. When I left, they were touring other African countries.

I wanted to be like them, inventing something that would really help people.”

Until then I had seen Tochuku as someone who was mostly withdrawn from the group, as someone who resented being stuck with us and hid from us amongst his technological projects. I had never thought about him as someone’s son and brother. He had been a brilliant little boy in a one-room school house, who happened to be exposed to a rare learning experience, and people who would feed his talents.

The fire crackled and sparks flew into the air, as if going home to the stars, while Tochuku stared into the flames a few moments before continuing.

“When I was 16, I was caught hacking into the Nigerian government’s computer, just for fun, not for any bad reason. The government didn’t put me in jail, probably because the computer company had a lot of money. Maybe they paid someone off. Or donated to some big cause. But the school principal said it would be best if I left the country. Because of my actions, I would always be under watch there.

We had already taken college entrance exams, and my mentors there wanted me to go to MIT. But my mother was already upset because I would be leaving all the way to come to the US. I had an older cousin in Silver City. My parents agreed that I could come here provided I lived with my cousin and went to Western, so he could keep an eye on me.

My teachers were not happy about this, because it was not as good of a school, but then they arranged for me to take classes at New Mexico Tech, in Socorro too, to supplement my learning. My sisters and parents had planned a trip to see me after I moved to Las Cruces. They were going to come for Christmas, but then the virus came.”

“I’m sorry you got stranded so far from your family,” I offered.

“Thank you. You lost your family too though, right? It has been a sad journey for us all,” he responded.

The next day dawned clear and bright, and after our usual brief, simple breakfast, we were on our way again. Victorio and I each had a bundle of Rabbit Sticks tucked into a bag so we could practice throwing them. It had been Victorio’s idea.

“Can you teach me how to throw Rabbit Sticks better?” he had asked that morning.

“It’s not that hard. It just takes practice,” I said.

“Yes. It is hard. You just happen to be really good at something very hard. You have a gift. So help me out. Don’t be stingy.”

As we rode along, I talked to him about how to hold his elbow at the right angle to use as a guide for aiming and flick his wrist with just the right amount of pop to get the sufficient velocity to kill a rabbit. We whacked stumps, rocks, and towards the end of the day, Victorio actually managed to hit a rabbit.

“You did it!” I exclaimed. “That was great, Victorio,” then in mock seriousness I intoned, “You are now a graduate of Lakshmi’s School of Rabbit Stick Throwers.” I handed him my last Rabbit Stick with a formal bow after he had tucked the still warm rabbit into his game bag.

Brother Matthew welcomed us like family when we arrived at the monastery, enveloping each one of us in his bearlike embrace as we dismounted. Stable hands attended to our horses while Matthew led us to the dining hall and asked someone in the kitchen to fix up a couple of rooms for us.

“Your plan is a good one, but it’s still risky,” Matthew was addressing Frank as we all shoveled a hearty hot stew into our mouths. The cooks had been delighted by our gifts of goat cheese, mesquite flour and other goods, and made sure we had the best of what they had to offer for our dinner. The smell of something sweet wafted in from the kitchen, and soon a plate of cookies arrived in front of us as well.

A quiet, smiling man carried a large teapot and filled our heavy clay mugs with a tangy concoction.

“Tell us what else we can do to make it safer then,” said Frank.

Matthew ran a hand through his thick black hair, mouth pursed in thought.

“Well, the Slavers don’t scout as much at night. Maybe if you left here in the morning, then made your way west and south, then hung out well outside of town until say midnight or so, you’d stand a better chance. The tricky part will be dealing with whoever is guarding the Maker compound.

You’ll need to get this letter into their hands before they bonk you on the heads,” Matthew handed Frank a letter of introduction, embossed with an old-fashioned wax seal imprinted with an image of the monastery. He also gave us another copy of the letter for the Uvies, whom we intended to see on the return trip.”

“Any suggestions on how to do that?”

Shaking his head ruefully, Matthew said, “I don’t know really. I guess as soon as you spot them, yell, ‘We’re friends of Matthew’s!’ If they spot you first, they might have you trussed up before you can say anything.

They aren’t particularly violent, in fact they don’t like using force at all, but they’ve had to toughen up over the years because they’ve had so many of their people taken by the Slavers. So they probably won’t hurt you, not much anyway. Just cooperate as best you can and hand them the letter as quickly as possible.”

It seemed simple enough.

This is an ongoing series from a forthcoming fiction novel by Laura Ramnarace.

Tune in weekly for the next chapter in ‘Sung Home’.

***

Laura Ramnarace, M.A. was driven to earn a master’s degree in Conflict Resolution while on her quest to find out why we can’t just all get along. She has published a book on inter-personal conflict, ‘Getting Along: The Wild, Wacky World of Human Relationship’, published a newspaper column also titled ‘Getting Along’, and submits regularly to Rebelle Society. Since 1999, she has provided training to a wide variety of groups on improving personal, working and inter-group relationships. ‘Sung Home’ is a work of eco-fiction set in southwestern New Mexico.