I Am More Than Just My Trauma: Life As Victims Of War Crime In Croatia.

‘Women across Borders’ is a global awareness campaign, shedding light onto the issue of sexual violence around the world. Photographer and executive producer, Stephanie Koehler, traveled to various Balkan states in 2015 to interview female survivors of sexual violence and experts in the field. Part of the campaign is a personal message from each survivor that is captured photographically. Her findings will be published in a series of articles documenting the stories of women in each of the countries she visited.

Read her articles on Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Montenegro (One and Two) and Kosovo.

***

Snježana, a mother of four in her 40s, is one of the courageous women who played an integral part in bringing justice to female survivors of the Croatian war through the new law Act on the Rights of Victims of Sexual Violence during the Military Aggression against Republic of Croatia in the Homeland War that finally grants these women the status of victims of war crimes.

The battle of Vukovar was an 87-day siege of Vukovar in eastern Croatia from August to November 1991; the war of independence from the former Yugoslavia ended in 1995. Snježana was a member of the sanitary unit in the Croatian army. When the war erupted, she decided to leave her firstborn behind with her mother, and fight for her country. She left without her mother’s blessings. She struggled with this for years, as she felt the violence she endured was a consequence of her leaving. Vukovar was completely destroyed, but has since been rebuilt. It remained in Serb hands until 1998.

Telling her own story has allowed her to better understand others who went through similar horrors. The atrocities she experienced are documented in the book Sunčica – Sunny and its accompanying film. The English version of it can be viewed on YouTube. To be one of the women who broke the silence, to speak up, took time, and did not come without its drawbacks.

Vukovar remains burdened by ethnic tensions. As if the horrors lived through during the war were not enough, many of the survivors still live in the same communities with their perpetrators and families. In Snježana’s case, her assailants’ criminal court proceedings were delayed by 12 years, and once they were finally incarcerated, they were released from jail awaiting their trial after only 1 week. One of them sold his home and fled to neighboring Serbia. The second one, a policeman, was let go due to a lack of evidence. He was suspended from his job only after she publicly accused him of the rape, but he continued to receive his salary. He, too, eventually fled Croatia. Both rapists were charged with a 6-year prison term, yet neither man served any of his sentence. Snježana is relieved that they fled the country, and thinks that this is better than having to live in fear of their release. Even so, the family of one of the perpetrators still lives in her hometown. In the past, her assailant’s family members would threaten her and her husband when they crossed paths in town.

In Croatia, many war criminals are released early due to good behavior, and are then fully supported by the government through benefits and social welfare. In Snježana’s opinion, this is a much better situation than many Croatians face in a downturned economy as they desperately search for jobs and a sustainable lifestyle.

At the time of the interview (May 2015) the newly established law for war victims was still pending, but has been in in effect now since January 2016. The Centre for Women War Victims (ROSA) in Zagreb, Croatia, was founded in 1992, and focuses on ending gender-based violence and women’s empowerment through economic and leadership workshops, support with legal services and counseling. ROSA has been a proponent of this law together with other women’s networks such as Snježana’s since 2009, and says that women still face obstacles to claiming victim status. They have to go through an extensive application process, and many re-live some of their trauma. Approved survivors are granted with a one-time payment of 100,000 Kuna (USD $15,172) and a monthly stipend of 2,500 Kuna (USD $379), receive free counseling, legal and medical aid. “Looking at neighboring countries, only women living in the autonomous Bosniak-Croat Federation have access to financial aid once they are approved as civilian victims of war. In Serbia women have to face lengthy application processes, which often keeps them from applying in the first place and in Kosovo, benefits for survivors are yet to be defined by the government even though a law was passed in 2014.” (source)

Although financial restitution is certainly a great step in the right direction, it doesn’t take away the scars the war inflicted on the women’s souls. Snježana and 16 other women did receive counseling over a one-year period funded by the United Nations Development Program (UNDP) some years ago. She expressed her gratitude, and said that this therapy helped her tremendously to change her outlook on life. She used to hate herself and have suicidal thoughts, but can now accept herself for who she is and enjoy life daily. “I now have a reason to live through my children,” she explains.

At some point, Snježana had confided in her parents only to hear that she had better not speak about her experiences. They felt it was embarrassing. One day she ran into her perpetrator and fell into a rage. She shouted at him and smashed her umbrella over his head. When her husband arrived at the scene, he had no clue what had just happened. He did not know that this was his wife’s rapist. She gives kudos to her husband who is now her biggest supporter. They have come a long way. Their relationship was greatly affected by the atrocities both of them experienced separately in the concentration camps. Although they were previously unable to verbalize what had happened to them individually, today they have an open dialogue.

At first, publicly speaking about her story was hard, but she is committed to continue to do so. She avoids speaking engagements in her community, but talked in Zagreb and around the country. Her daughter was recently asked at school why her mother was publicly and deliberately seeking financial aid. Surely this is a wonderful sign of possible social change; several Serb kids came to her support and made sure she was doing okay. A testament that change is possible.

Together with three other women, Snježana formed Udruga Žene u Domovinskom Ratu (Association of Women in Domestic War) that works closely with female and male survivors of sexual war violence, and also offers creative workshops. The association has 30 members and offices in Zagreb and Vukovar. All are survivors. Her dedicated work for her association, speaking engagements, and of course her family, keep her busy.

When asked about commonalities in women’s lives as survivors, Snježana points to stigmatization. To this day, there are people who laugh about them, including women! Those who at first showed great support withdrew once they heard that Snježana and her friends were seeking financial restitution for the war crimes inflicted on them. In light of the financial gain, one woman even suggested that these women stay victims if they truly claimed to be one rather than seeking justice. This part was especially hard for me to hear, and yet the tendency to blame victims is so common worldwide. As women, we can be each other’s greatest supporters, and unfortunately, we can also be our worst critics — putting each other down versus standing behind each other. Infuriating! There is much need for change in that regard. I believe that this is not just true for horrific stories such as Snježana’s, but typical everyday situations where, out of jealousy, fear or greed, women opt to withdraw from another woman, or refrain from supporting her in her endeavors.

The goal of Snježana’s association is to show the world that they were victims of war, and that there were in fact crimes committed. She suggests that the society needs to change from its roots, and she believes that faith can be that agent of change. When she was awaiting her perpetrators’ court proceedings, she at some point had to hand over her fears and worries to God to pull her through a grueling 12 years of court battles. During this trial, the judge ordered a psychological evaluation of her. The resulting evaluation showed that she had a very high IQ, but it went on to comment that her speech was strange. Snježana explained that this strange speech was really her praying during the court sessions. Even in this situation, a woman practicing good self-care is judged harshly, and it is insinuated that she is not a trustworthy character.

Her faith transformed her life. When she once wanted to take a pill to forget about her pain, she now says, “I am more than just my trauma!” Undoubtedly she has proven that through all she does today. I am so taken by the transformation she underwent and the strength she exudes. What a humbling experience to be in her presence.

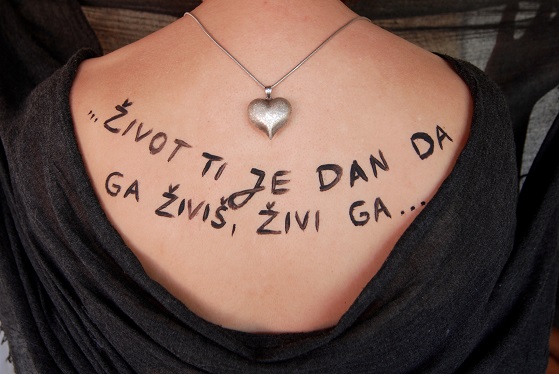

For her quotation, she chose “Life is given for you to live — so live it!”

A special Thank You to my dear friend Kim Birdsong for her support in producing the articles in this Balkan series.

***

Stephanie Koehler is a journalist and photographer residing in California. Her goal of ‘Women across Borders’ is to unite women all over the world to document the pain they endure as a result of sexual violence and the healing approach they take to grow from victim to survivor. Her work started in the U.S. and took root in form of interviews with women in various Balkan States and Germany. Her articles include photo essays of female survivors, and are platforms to tell their story. Her former work can be read on The Women’s International Perspective. Stephanie’s vision is to grow this work into a global sexual assault awareness campaign.