An Assertion of Woodstock as a New Sermon on the Mount. {Part 1 of 2}

At its conclusion in August 1969, the Woodstock Music & Arts Fair looked like an abandoned refugee camp in the aftermath of a flood.

The mud-caked blankets that littered the ground likely had been dropped by the U.S. Army, along with food, water and medical supplies, after the site was declared a state of emergency. Some see Woodstock as a shithole. I see it as a religious gathering as momentous as none since the Sermon on the Mount.

I see Woodstock as a three-day ceremony, and celebration of a major paradigm shift in human consciousness, one which incorporated all the movements and changes in society up to that time, and rocketed them forward.

At present, sadly, a shift in the opposite direction is gaining ground. I see the example set by Woodstock as an antidote to that. As is said also of Christ’s Sermon, Woodstock, I believe, offers us a model for how to carry on.

***

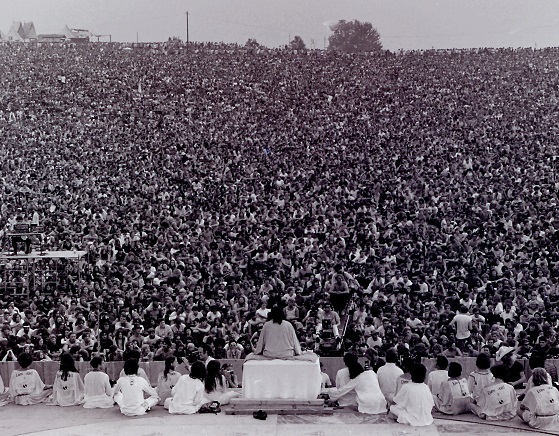

Think of it. Half a million people packed like sardines on a plot of undeveloped land for three whole days. People thronged to Woodstock in numbers so great they caused gargantuan, 20-mile traffic jams. Desperate, they abandoned their vehicles and struck out on foot. The true Woodstock wasn’t organized, it happened organically; it birthed itself as an open-air cathedral to which hundreds of thousands flocked.

Think of the unwashed bodies. The stench of overflowing sanitation facilities. The food shortage. It was August, it was hot. Water was scarce. In the stifling heat, a group formed a circle by a teepee and did a rain dance. It seems their prayers were answered, tenfold: the clouds burst open and decided not to close, inundating the festival-goers in a collective, ongoing bath (or maybe baptism).

It’s not hard to imagine the physical discomfort of living in a pop-up city of five hundred thousand during a monsoon. Concert-goers on the ground were advised calmly, from the stage, to sit calmly beside their neighbors and ride the storms out, which they did. Despite what by all accounts were hellish conditions, people behaved… well, like Christians.

The storms passed, the sun came out again. When word got back to town that there wasn’t enough food to feed everyone at Woodstock, the townspeople got busy. Local businesses donated food. Volunteers made thousands of sandwiches. Nuns distributed them. The shithole was transcended.

***

Woodstock came close to being aborted. Perhaps one of the more harrowing moments arrived in July 1969, a month before opening day, when the citizens of Wallkill, NY got wet feet about hosting a large gathering of hippies. The town rescinded the permit it issued months earlier, leaving festival organizers scrambling at nearly the eleventh hour.

Serendipitously, another site was soon found. The same week that Neil Armstrong walked on the moon, Woodstock co-founder Michael Lang was led to Bethel (Hebrew for ‘House of God’), about 50 miles from the original site. “It was magic,” Lang said. The new site was far superior to the abandoned industrial park in Wallkill which Lang had never liked anyway.

Here, on Max and Miriam Yasgur’s dairy farm, were rolling green hills, a lake, even a big earthen bowl in the middle of it all — a perfect natural amphitheater. Lang was ecstatic.

But the move created difficult deadlines and disorganization. A week before the festival, organizers had to make a difficult choice: complete the security fence or the stage, they couldn’t have both. Naturally, they chose the stage. Although, security at the festival was a real concern. Many were worried about the possibility of a riot at Woodstock, including its producers.

To provide security, arrangements were made to hire a few hundred off-duty New York police officers to work the festival. But Lang and co-producer Artie Kornfeld remained uncompromising in their demand that any security force be unarmed.

When the NY police commissioner issued reminders to his employees that moonlighting was prohibited, instead of off-duty, unarmed cops, members of the Hog Farm commune in New Mexico were hired to keep the peace as well as provide food. They called themselves the please force.

Half a million people in the mud and the rain for three whole days, and hippie cops without guns, and so much peace, love and music coursing through the ether on Yasgur’s farm it left no medium for violence to take root.

Joni Mitchell wrote, “Woodstock was a spark of beauty. Some white, middle-class kids popped some Owsley LSD and saw that they were part of a greater organism.”

Jimi Hendrix later wrote in a poem: “500,000 halos outshined the mud and history. We washed and drank in God’s tears of joy. And for once, and for everyone, the truth was not still a mystery.”

And this from Jerry Garcia J: “It’s amazing, man, it looks like some kind of biblical, epochal, unbelievable scene.”

Needless to say, much at WS did not go as planned. Rain fell on live wires, stages threatened to collapse, and people climbed on towers which looked fragile in the storms. But how much the better for it, perhaps, were some of the stage performances.

Singer-songwriter and guitarist Richie Havens, for example. Because the Indian spiritual leader who was scheduled to do it got stuck in traffic, festival organizers turned to Havens to give the invocation. Which he did, of course, with song. But he couldn’t stop there. When he finished his set, Havens was told the next act hadn’t made it in yet either. So he had to give a sermon too.

After four encores, three hours of performing nonstop, and utter depletion of his repertoire, Havens improvised the spiritual “Motherless Child” with the gospel song “I Got A Telephone In My Bosom” and gave birth to the now famous “Freedom.”

Finally, the swami arrived. He spoke softly, with humility. Swami Satchidananda told those assembled that America has helped the world with materiality, but now it must help the world with spirituality.

On Friday night, Indian classical composer Ravi Shankar, known for his disapproval of the drug scene, performed reluctantly in the rain. A stoned young Arlo Guthrie followed, closing his set with “Amazing Grace.” The music played all night, lifting people’s spirits. Music kept the peace. And when it was time to go to sleep, Joan Baez tucked everyone in with “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “We Shall Overcome.”

On Saturday, with the instrumental “Soul Sacrifice,” Santana took the crowd to church like nobody’s business. Visiting the site years later, Carlos Santana, leader of the rock-Latin music band Santana, will weep. “This was ground zero for peace and love,” he’ll say.

Alan Wilson, the humble, sweet-faced boy in Canned Heat, played an old yellow guitar with an STP sticker on it. Something about his clothes, his hair, he looked Early American Heartland. He looked innocent.

Late Saturday night, when Janis Joplin took the stage, she revealed herself to be a shapeshifter: singing into the darkened microphone, she looked tormented, like a wounded daughter, like a crone. Lifting her face to the light, she was luminescent, an angel. Joplin sang “Work Me, Lord” as a feminist lament directed first at God then an earthly man. She sang the pang and pain of every woman, whether they knew it or not.

In the wee hours of Sunday morning, Sly & The Family Stone performed. In his book, Back to the Garden: The Story of Woodstock and How It Changed a Generation, disc jockey Peter Fornatale referred to Sly Stone as one of the “high priests” of Woodstock. Stone looked the part as he strutted in his white fringed coat, raising his arms to the heavens. He gave a sweet sermon. He led call and response.

And on Monday morning, Jimi Hendrix gave a fitting benediction. In his stunning improvisation of “The Star-Spangled Banner,” Hendrix told our war- and battle-torn story, capturing the emotion associated with it, from the beginning until then, that dawn at Woodstock.

There was a long roster of stars offstage at Woodstock too, people who kept busy looking out for the common good. Wavy Gravy (Hugh Romney) and the Hog Farmers managed to maintain mass calm while also feeding the masses. By being simply a calm, grounded and supportive presence, Romney’s wife Bonnie (now Jahanara) comforted and guided trippers through bad experiences in the “freak-out tent.”

The teens of the 1950s and ‘60s were the first generation to cleave a fissure in the edifice of the patriarchy. This inevitably led to protest, though at Woodstock it was muted. Country Joe McDonald, in protest of the war in Vietnam, began his call and response with: Give me an F!

In photographs and film footage, posters with feminist and environmental themes can be spotted. But when politico-social activist Abbie Hoffman entered the stage spewing anger, Pete Townshend bopped Abbie on the head with his guitar and that took care of that.

When concerns about riot and violence proved unfounded, Artie Kornfeld referred to the entire gathering as “family.” Both he and Lang believed they’d been part of something sacred. One morning as they watched the sunrise, I can’t remember who, it might have been stage/lighting designer and master of ceremonies Chip Monck, somebody told the crowds that God was their lighting man. I find it credible.

This is the first of a two-part excerpt from a forthcoming book, titled

“Getting Back to the Garden: An Assertion of Woodstock as a New Sermon on the Mount +Other Wild Notions”.

Read Part 2 here.

***

Debra A. Copeland is an independent author, seeker, grandmother, Reiki healer and spiritual activist who, for the first time in her life, has ample hours to write, a life change which fills her with joy! She lives with her husband in the Virginia Piedmont, in a small house being overtaken by a large body of unfinished work, and looks forward to spending the rest of her life completing each project, spending quality time with loved ones (especially her grandchildren), and (out of concern for the future of all children) working for human and environmental justice and transformation. You could contact Debra via email.

***

{Join us on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram & Pinterest}

Comments

Comments are closed.

An Assertion of Woodstock as a New Sermon on the Mount. {Part 2 of 2} | Rebelle Society

May 28, 2019 at 7:00 am[…] the Garden: An Assertion of Woodstock as a New Sermon on the Mount +Other Wild Notions”.Read Part 1 […]